Overview

- It’s easy to think quite narrowly about information advantage. But even inside strict military environments, a cross-discipline, platform-based approach is now essential.

- The aim is a more open ‘hive mind’ – a grid integrating structured and unstructured data; new sensors and sources; and insights delivered where they make a difference.

- That poses questions about how systems, networks, platforms and human resources that secure and exploit information advantage are designed, procured and deployed.

- But get it right, and the model is incredibly adaptable. The new ways of thinking about information advantage – including protections for data privacy and security; and bias – can revolutionise the broadest interpretation of ‘national security’ right down to local policing and border management.

The history of progress is all about doing more with less. More crops with fewer farmers, freeing people from seasonal toil. Multiplying the amount of fabric produced by the same number of weavers. Getting more mileage out of combustion engines; or more power with less CO2 emissions.

‘More for less’ also sits at the heart of innovation in national security We face more diverse and more diffuse threats than ever before. It’s harder to decide where the line between hostile state actor and organised criminal lies. Civil protection and policing meld with border security and even trade policy in ways that make siloed thinking outdated.

Tackling these diverse situations with limited resources – especially in a world shaped by budget restraints in the wake of recovery from Covid-19 means making better use of the information we gather and sharing it more effectively across domains. If we can do more at each national security ‘touch point’ with less resources, greater overall effectiveness can be achieved. This is partly about more capable systems for less money – a classic technological gradient. Partly sharing information more intelligently, ensuring data collected is well analysed and used wherever it’s meaningful. And also diverting resources away from less effective activities towards the things that make a difference to citizens.

It’s all about COP

Bringing together different agencies that deliver against a broad ‘national security’ mission means developing a more sophisticated and responsive ‘Common Operating Picture’. (COP is originally a military acronym, “a single identical display of relevant information – troop positions, status of infrastructure and so on – shared by more than one command.”)

The easiest way to explain how that delivers more for less is to look at the UK’s largest police service – such as the Metropolitan Police Service in London. With limited human assets, getting officers to the places where they are needed is critical. For the safety of citizens, fast response is key.

A city such as London also faces very varied situations – from low-level vandalism and unauthorised street trading at one end of the spectrum, to serious domestic violence and terrorism at the other. Some demand immediate officer intervention, often specialists (in even shorter supply); others a regular passive presence. Today, officers must pound a ‘digital beat’ as much as they do the capital’s pavements.

That’s where a COP comes in. It comprises a series of layers. First, the environment itself – the physical aspects of a city. Second, historic crime patterns and human intelligence, analysed to provide insights on likely ‘behaviour’ of the city. This helps assign resources to optimise preventative policing. Third, real-time surveillance through technology such as CCTV (5G will have a transformative impact here) beat observations and intelligence reports can be analysed to provide a view that allows resources to be directed swiftly to situations where citizen security is at risk.

With a platform approach, we can add a fourth layer – the location and status of national security personnel who might action the information and analysis, further allowing for smarter allocation of resources.

More value for money

UK agencies and national security decision-makers can learn a lot from the US experience. With more large cities (and, arguably, more acute domestic security issues, such as gun crime), forces there have been at the forefront of investment in technology to create multi-layered information advantage.

Gunfire clearly demands fast response. Being able to direct officers to the location of gunshots – even sniper attacks or drive-by shootings, where the assailant might not be obvious to witnesses – is a big plus. Critics of these systems, including senior officers, argue they create too many false positives. Better, real-time, integration of the data generated within a broader COP, with more refined context using smarter information advantage – might solve the problem.

While the number of cities in the UK with a need for such systems is much lower, deploying similar tailored approaches to data collection, analysis and exploitation could reap dividends across a wider field of play. Yes, UK policing is administratively quite fragmented but the National Crime Agency, for example, can still reap significant benefits from the aggregation of data, smarter analysis and enhanced information advantage.

Areas such as organised crime, the ‘County Lines’ drugs trade, cybercrime and fraud are obvious targets. Giving local forces a national context – that broader information advantage – for their own decision-making is also hugely valuable. Former Met Deputy Commissioner Sir Craig Mackey describes this an ‘enterprise view’: “the ability to see and understand policing across the whole of UK public and private systems”.

Picking winners

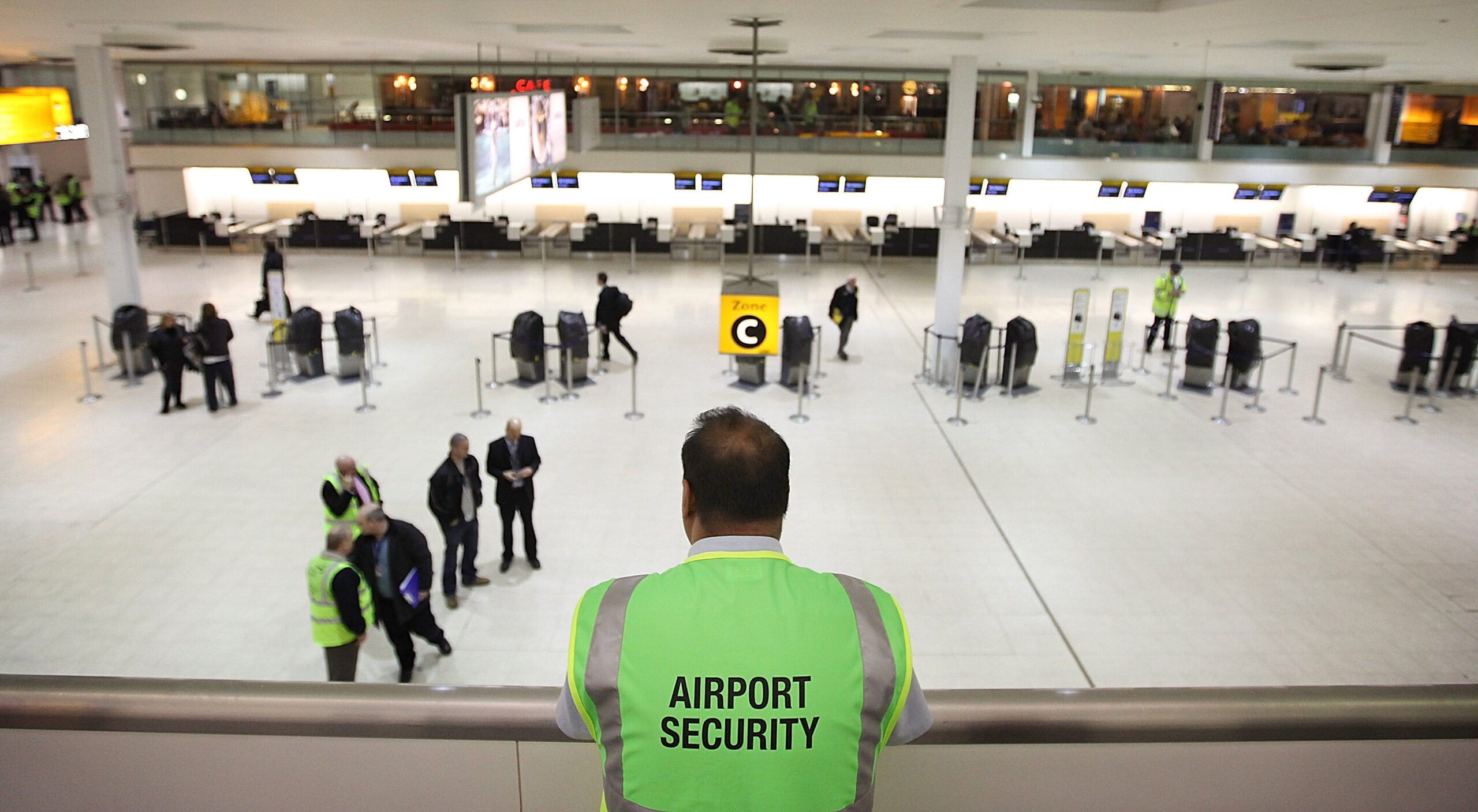

Border security presents a slightly different set of challenges. In many scenarios in the past, the touch-point has been fixed – a customs post, passport control, a port – but the volume of interactions is now much higher and combined with the expectation of a contact-less and frictionless border. Again, the requirement is to focus resources on high-probability cases, making more effective interventions with limited personnel.

The same idea of smart analysis of existing data, enhanced situational awareness and adaptable technology works here, too. At Leidos we’ve been supporting border forces with this approach for more than five years – integrating advanced scanning solutions, generating and using information advantage compiled from different domains to speed up throughput and triage vehicles and passengers, picking out high-probability targets for deeper inspection. The major investment in new border technology should see this work paying richer dividends.

We also layer in artificial intelligence to both enhance the underlying analysis – boosting the information advantage for border forces – and automate many of the functions at those touch-points. Non-intrusive scanning of vehicles (our platform is called VACIS) can be augmented with automatic monitoring using machine learning technology to ensure that data is captured more efficiently, fine tuning the system themselves and feeding back more granular analysis to inform human decision-making and resource allocation.

Leidos has learned a lot about how automation speeds up and makes those kinds of inspections more efficient from seemingly unrelated sectors. For the past five years, for example, we’ve been working with i-Tech 7, an offshore oil and gas infrastructure maintenance company, to integrate historic pipeline performance data with AI analysis of real-time pipeline scans. The result? More inspections at lower cost, with fewer disruptions and more proactive maintenance. It’s a COP for the flow of oil.

The big picture

While some technological interventions are highly specific to situations or locations, others hint at the possibilities for information advantage to operate across multiple domains of national security –it’s not just policing and borders, but other regulatory agencies and social provision. Biometrics is a good example. Fingerprints and facial recognition can be powerful tools from the most mundane uses – building entry much more critical cases, such as monitoring known bad actors.

So when we talk about information advantage in the national and domestic security space – as opposed to the military domains – we also need common sense, safeguards and scrutiny. Technology can certainly help us here and we are working with new levels of protection and auditability to give national security organisations the common operating picture they can benefit from with those safeguards.

That’s crucial because enhanced situational awareness, new capabilities in artificial intelligence and broader COP is giving front line officers the opportunity to do more with less. That’s good news for every stakeholder.

For more information, visit leidos.com/uk-national-security