As Russia’s ongoing invasion of its neighbour Ukraine crystalises the reemerged awareness of the dangers of active military operations again on the European continent, the digital domain and cyber operations are comparatively less understood.

Perhaps one of, if not the most critical, pieces of national infrastructure is the network of global navigation satellite systems (GNSS) which can help move societies along, while also being relied upon in certain areas for parapublic and military use. In Europe, Russia is active in its disruption of GNSS services and has embraced cyber warfare and the digital domain for so-called grey operations, security activities that fall below the threshold of outright conflict.

How well do you really know your competitors?

Access the most comprehensive Company Profiles on the market, powered by GlobalData. Save hours of research. Gain competitive edge.

Thank you!

Your download email will arrive shortly

Not ready to buy yet? Download a free sample

We are confident about the unique quality of our Company Profiles. However, we want you to make the most beneficial decision for your business, so we offer a free sample that you can download by submitting the below form

By GlobalDataWe spoke with Ganesh Pattabiraman, co-founder and CEO of geolocation service developer NextNav, on how the global security environment is changing and the threats posed to GNSS and satellite services in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and an apparent reshaping of the global world order.

Richard Thomas (RT): How are the threats to Global Positioning Systems (GPS) and satellite connectivity changing? Is this a reversion to the Cold War-era environment or are we facing different threats now as then?

Ganesh Pattabiraman (GP): As war rages on Europe’s eastern front and hostilities with Russia are at a level not seen since the Cold War, recent months have brought security threats – including cyber and military – into sharp focus. However, threats to navigation systems are rarely discussed.

Global navigation satellite system (GNSS) signals around the Russian border and in and around Ukraine have been consistently jammed and spoofed to support the Russian military offensive. Whilst the idea that such action would be taken against the UK and its infrastructure may have seemed improbable at the start of the year, so was the thought of war on the European continent in the 21st century.

See Also:

The Russian state has been responsible for a litany of hostile activity. A 2019 report by a Washington, DC, think tank documented more than 10,000 cases of GPS interference in the last five years from Russia, including noting that [Russian President Vladimir] Putin is intentionally spoofing his location and jamming GPS signals whenever he travels.

More recently, in November last year, Russia shot down its own satellite in a warning to the West, announcing on state television that they could take out all of the GNSS satellites used by NATO. In June 2021, Royal Navy warship HMS Defender had its GNSS and Automatic Identification System (AIS) spoofed so it looked as if they were in the Crimea headed towards a Russian military port when they were in fact in Ukraine. As a result of these recent attacks, EU’s Aviation Safety Agency is now warning of GNSS spoofing and jamming in aircraft with noted incidents in flights over Europe.

It is worrying that the UK is currently the only United Nations Security Council member who does not have either sovereign GNSS capability or PNT service backup

Ganesh Pattabiraman, CEO NextNav

It is clear that we are facing different, more diverse, and more technologically advanced threats than during the Cold War – particularly given our reliance on GNSS is far greater than it once was. Threats to GNSS security and resilience have made it a single point of failure for critical national infrastructure, and the looming possibility of a large-scale disruption could have dire consequences both militarily, and on the civilian population. As such, defence ministers and intelligence analysts in both the UK and US have raised alarm.

The economic impact of a GPS outage cannot be overstated. According to a UK Space Agency report, it is estimated that 11.3% of UK GDP is supported directly by GNSS across financial markets, transport, logistics and more. At a conservative estimation, the economic impact of such a disruption to GNSS would cost the UK nearly £2bn a day. A glitch of just 100,000th of a second can cause huge problems – leaving container ships stranded, shuttering the stock market, leaving ATMs inoperable, and cell phone calls without a reception. Even more critically, the loss of GNSS would have severe and life-threatening effects, such as getting ambulances to patients or getting power to homes and hospitals around the country.

RT: How is ground-based positioning, navigation, and timing (PNT) more resilient than satellite-based systems?

GP: Satellite-based systems are vulnerable to our adversaries and to natural effects, including solar flares (which have also caused disruptions in the past). GNSS’ lack of signal power makes the technology vulnerable to jamming, the lack of encryption has led to spoofing, and the whole system’s reliance on ‘sitting duck’ satellites all demonstrate GNSS’ vulnerability further.

Not only do we need to build resilience to our existing satellite infrastructure but also through alternative solutions that function in instances of GNSS blackouts. The solution to building that resilience is not a matter of innovation. The solutions already exist.

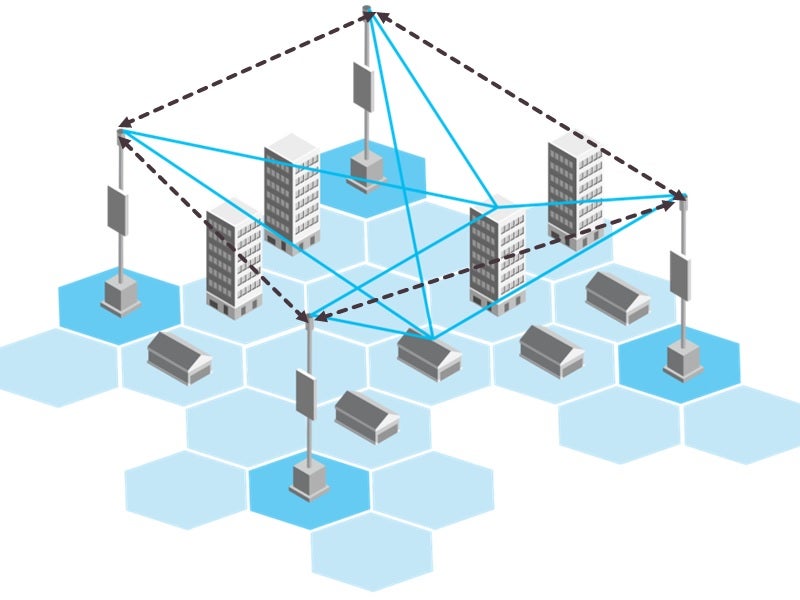

Ground-based PNT technology provides that back-up function and more. Think of it like a GNSS satellite on the ground. With a few well-placed beacons/transmitters that can be controlled within the borders of the UK, these can cover entire cities with encrypted signals that are 100,000 times stronger than GNSS. Such a network complements the GNSS services that power the UK’s truly globalised economy in which both traders in the City [of London] and high street bank tellers rely on a universally referenceable time source.

A metropolitan beacon system extends the operational reach of resilient, secure, reliable PNT services, providing the UK economy, and the international financial markets on which it is built, with an added layer of protection and ensures an uninterrupted service. In addition, this would also add an additional layer of resilience geolocation services used by military personnel and the security services.

Resistant to spoofing and jamming, ground-based PNT solutions also reach inside of buildings and into urban areas that GNSS can’t [reach], resulting in more available, more resilient, more accurate PNT services that underpin so much of our critical infrastructure.

Simply put, a ground-based PNT system would give the UK Government true sovereignty over our critical national infrastructure and, while GNSS infrastructure might be out-of-sight, it cannot remain out of mind.

RT: How capable is Russia and China’s PNT and GPS jamming capability? In your view, how willing are these two countries to be involved in jamming GPS/PNT and other activities perceived to be below the threshold of war?

GP: The Russian and Chinese GNSS jamming capabilities are clearly advanced. We have seen attacks on geolocation services play out across battlefields in Ukraine and Syria as well as impact neighbouring countries like Finland, Israel and the Baltics, who have reported jamming “spill overs”.

There are known reports of GPS jamming along the South Korean border, which led to South Korea implementing terrestrial-based systems to complement GNSS. Understanding the threats in Japan and potentially applicable to transportation and critical infrastructure, a Japanese partner of ours has set up a trial system in Japan. The Japanese Government has allocated 5MHz of spectrum to them to assess the Metropolitan Beacon System.

Given these threats, the West would be wise to press ahead and implement a viable strategy to address emerging and long-standing threats to satellite-based GNSS, through multiple resilient layers and technologies.

RT: What work is NextNav doing in this sector, and what conversations have been had with the US and UK in adding greater capability to PNT systems used for military operations and critical civil national infrastructure?

GP: We have held conversations with leading governments across the West to provide the next generation of geolocation position, navigation and timing services that are more available, more resilient, and more accurate.

Within the US, there are several activities underway both in the Department of Defense (DoD) side as well as the civilian side. On the DoD side, the US Government has developed a two-year plan to evaluate alternate PNT systems, on the civilian side the Department of Transportation conducted a test in 2020 that evaluated over 11 alternatives to GPS systems. Congress, in the 2022 budget, allocated additional funds to the US Department of Transportation and Department of Homeland Security to take the next steps on PNT resilience.

The British Government is currently reviewing alternative navigation systems to boost resilience and support its critical national infrastructure and will publish a forthcoming PNT strategy in the coming months. Proposals under consideration will address ground-based alternatives and include NextNav’s technology among others.

It is worrying that the UK is currently the only United Nations Security Council member who does not have either sovereign GNSS capability or PNT service backup, and allies such as France and the US are also exposed with no backup PNT system. Establishing one has never been more pressing, and as the conflict in Ukraine endures, Russia continues to provide ample evidence that, as we continue to bide our time, the threats to our everyday life continue. It is clear that now is the time for the UK and US governments to press ahead and implement a viable strategy to address emerging and long-standing threats to satellite-based GNSS. Without that resilience, the very technologies, products, and services that we all depend on are vulnerable to disruption.