- The new US National Defense Strategy has set out the geopolitical aims of the United States in the years ahead

- Much focus goes to Europe and Nato, with the US seeking to decouple itself from the continent’s security

- China, Russia, Iran, and Greenland all feature prominently, but there is no space for Taiwan or Australia

The recently released US National Defense Strategy, coupled with the comments made by President Donald Trump in Davos, added further structure to an emerging New World Order as Washington detaches from generational commitments.

In loose terms, this means removing as much conventional US military capacity as is possible from Europe, turning its Nato members into customers and recipients of American products and intelligence, less so strategic partners.

Discover B2B Marketing That Performs

Combine business intelligence and editorial excellence to reach engaged professionals across 36 leading media platforms.

The US pivot is both inward – to secure what it considers to be threats in its own borders – and also ensuring American hegemony over its near abroad. The wider international pivot will see an increasing focus on China and ensuring access to the markets in the Indo-Pacific.

“Crafting a defence strategy requires setting priorities. When reading the 2026 National Defense Strategy, it is clear that the administration views the Nato alliance as a relatively low priority,” warned Fox Walker, defence analyst at intelligence firm GlobalData, in a prescient instance of analytical foreshadowing.

Here are the Top 5 highlights from the National Defense Strategy, and some of the possible implications.

America First

Securing the homeland and the near abroad, the America First strategy is intended to enable continued US dominance of its borders and immediate region, particularly related to access from the Pacific to the Gulf of America through the Panama Canal.

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalData“We will secure America’s borders and maritime approaches, and we will defend our nation’s skies through Golden Dome for America and a renewed focus on countering unmanned aerial threats,” the NDS.

Further, the NDS stated that the US military would “guarantee” access to “key terrain”, mentioning by name the Panama Canal and the Gulf of America (nee Mexico).

The intention of the US to dominate its neighbours has been clear since the return of President Trump, engaging with diplomatic spats with Mexico and Canada, and demonstrating its willingness to utilise military force to achieve its aims, as seen in Operation Absolute Resolve in Venezuela.

“We will engage in good faith with our neighbours, from Canada to our partners in Central and South America, but we will ensure that they respect and do their part to defend our shared interests.

“And where they do not, we will stand ready to take focused, decisive action that concretely advances US interests,” the NDS states.

Europe and Nato

“Ours is not a strategy of isolation,” the NDS states, apparently without irony, charging European partners to take the lead for conventional security on their continent.

The strategy continues to extol the messaging emerging from the White House since the return of President Trump, namely that European countries have been freeriding under the security blanket provided by the US military.

Albeit undiplomatic, this perception is not entirely inaccurate. It is fair to say that defence budgets of Europe have been artificially supressed due to the presence of conventional US forces in the continent, a situation that is only now beginning to change, following last year’s acrimonious Munich Security Conference.

“For too long, allies and partners have been content to let us subsidise their defence. Our political establishment reaped the credit while regular Americans paid the bill,” the NDS said.

Far from wanting to ensure of more balanced sharing of defence responsibilities, the US policy to Europe is one of containment, urging European capitals to concentrate on the regional, less so areas that might compete with US market aspirations.

“We will be clear with our European allies that their efforts and resources are best focused on Europe,” the NDS explains.

Europe is also encouraged to buy US military equipment, maintaining the national markets as defence customers rather than military partners, with America seeking only to provide “critical but limited” security support.

“We will also seek to leverage Nato processes in support of these goals, while also working to expand transatlantic defence industrial cooperation and reduce defence trade barriers in order to maximise our collective ability to produce forces required to achieve US and allied defence objectives,” details the NDS.

However, the US strategy is fraught with risk, according to Walker, who suggests that such an approach could present at least two potential negative outcomes.

“On one hand, ‘critical but limited support’ may not be enough to dissuade Russia and other adversaries from pursuing their territorial ambitions,” said Walker.

Continuing, Walker contended that a Russian breakthrough against Ukraine, if caused by US isolationism, would “shatter America’s standing on the world stage” and likely lower President Trump’s approval rating at home.

“On the other hand, a strong and independent Europe will limit American influence on the continent and thus in the world. America risks lowering itself to the status of a regional power if its relative power wanes compared to that of Europe,” Walker added.

Iran-Russia-China

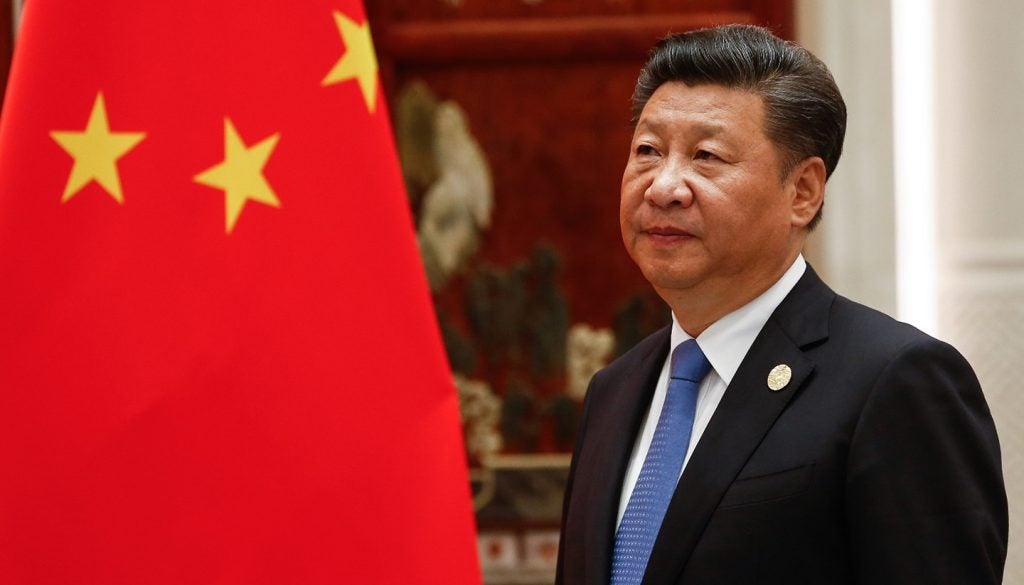

On relations with the trip of Iran, Russia, and China, the US approach is distinctly different from the previous administration of President Joe Biden. Indeed, regarding China, the US approach is far more business-like, seeing Beijing as a necessary partner in the new Great Game.

Notably, Taiwan is not mentioned once in the document.

“We will be strong but not unnecessarily confrontational,” the NDS details, with the US seeking a “stable peace, fair trade, and respectful relations with China”.

Interestingly, the US will look to establish greater military-to-military communications with China’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA), with a focus on strategic stability. “Our goal in doing so is not to dominate China; nor is it to strangle or humiliate them,” the NDS states.

Quantitatively, the PLA Navy (PLAN) has long-since surpassed the US Navy in terms of active surface combatants and is rapidly gaining ground in the subsurface domain. In addition, as China’s moves quickly through generational developments of warships – effectively more quickly iterating from a Batch 1 design to a new Batch 2 as technology evolves at pace – the qualitative gap is also being compressed towards the point of parity.

The US maintains its strategy to affect a “strong defence denial” with the First Island Chain region, in a bid to ensure continued US access to the Western Pacific. This is one area where there could be potential for friction, as China will continue to break out and dominate regional waters and politics.

Russia is mainly categorised as a European competitor, with the caveats of its Arctic operations and Pacific shoreline. The NDS language paints Russia as a “persistent but manageable threat to Nato’s eastern members for the foreseeable future”, a pertinent choice of language as it shifts responsibility for European security to Europe itself.

The US Department of Defense (nee War) is tasked with ensuring “that US forces are prepared to defend against Russian threats to the US homeland”, claiming its forces will continue to play a role in Nato, “even as we calibrate US force posture and activities in Europe… to better account for the Russian threat to American interests”.

Translating, the appears to suggest the US will retain strategic capabilities in Europe to secure the continental US through access to assets like RAF Fylingdales space warning system in the UK, and stationing of tactical nuclear weapons in European airbases, potentially also in the UK at US bases like Lakenheath.

It is known that conventional US military capabilities are being drawn down, with reductions in Eastern European countries such as Romania. The US also wants to shift command of Nato to a European military power, probably shared between France and Germany. France already has a guarantee that certain high-level Nato positions are reserved for French officers, and such as structure could be extended.

“The National Defense Strategy mischaracterises Russia’s war against Ukraine as ‘a protracted war in its near abroad,’–in reality the conflict represents a threat to global order. The document is correct to say that ‘Moscow is in no position to make a bid for European hegemony,’ but this misses the greater, long-term danger of Russia’s invasion,” Walker considers.

Rather, success of Russia would send a signal to autocrats elsewhere that if they fight hard enough, they can claim sovereignty over neighbouring territory.

“The destruction of Ukraine would usher in a more dangerous era, one in which leaders no longer feel as restrained by the principle of nonaggression that defined the post-war order,” Walker said.

Less is mentioned of Iran, centred mainly on the desire to prevent Tehran from acquiring a nuclear weapon, citing the 2025 strikes on Iranian nuclear facilities as examples of Washington’s approach. Israel is praised as a model ally, with US regional efforts at pains to secure its relationship with its long-time Middle East partner.

However, Iran remained a threat, despite the air strikes of 2025 and the “degraded” capabilities of its proxies Hezbollah and Hamas following Israel’s Gaza war and strikes into Lebanon.

A clear example of the new transactional US approach to politics is made in its reference to “partners” in the Gulf region, who are described as being “increasingly willing and able” to defend themselves against Iran and its proxies, pertinently thanks to the “acquisition and fielding a variety of US military systems”.

In purchasing US military equipment, Gulf countries are provided “even more opportunities for us to enable individual partners to do more for their defence” and “foster integration” between regional partners.

“America is less safe and less powerful in an international system that disregards national sovereignty,” Walker concludes.

Greenland

The US has its sights set on Greenland in a desire to what it says is secure its Arctic interests, putatively security related, but doubtless containing an economic and Great Power element.

Claiming that US interests are under threat “throughout the Western hemisphere”, the NDS seeks to position American territorial ambitions as necessary “in order to safeguard our nation’s own economic and national security”.

Further, with “adversaries influence” growing in Greenland, among other locations, the US appears to be reserving the right to act.

“We will guarantee US military and commercial access to key terrain, especially the Panama Canal, Gulf of America, and Greenland,” the NDS continues.

How the Greenland debacle will lay out is yet to be seen, with Europe rallying around Denmark, which administers the island as an autonomous territory. At the recent Davos gathering, President Trump stated that Washington would not use force to acquire the territory.

All well and good, but should the US choose to, there is little Greenland, Denmark, or European Nato could do to stop it.

Australia and AUKUS

Remarkably, the NDS did not contain a single reference to Australia, the leading Anglosphere representative in the Indo-Pacific region, nor the putative endeavour to establish a nuclear submarine capability operated by Canberra under the AUKUS programme.

Originally signed under the Biden administration, the future of AUKUS with President Trump once again resident in the White House is uncertain.

Aimed at delivering a new nuclear power to the defence battlespace, the trilateral AUKUS endeavour is one of the most ambitious programmes in recent memory involving the transfer of secretive submarine technology and generation of an entire sustainment ecosystem.

However, as a trilateral government-to-government-to-government enterprise, with each of the US, UK, and Australia having their own separate defence procurement structures, one problem looming over the horizon could be an AUKUS programme attempting to deliver by committee, amid a lack of accountability.

The difference between accountability and responsibility is subtle but effectively allows responsibility to be delegated to complete specific elements of a programme, while those accountable have to deliver the system as a whole.

In AUKUS speak, each partner nation in responsible for the delivery of specific elements of their own contributions, be in nuclear technology, design, sustainment, or training.

However, these countries are not individually accountable for the delivery of the programme as, which instead appears to rest on a series of US, UK, and Australian military and government committees that periodically gather to catch up.

The weak link appears to be the UK, with its own nuclear submarine sector struggling for industrial capacity and chronic availability issues of boats in service.

Don’t be surprised if the US gets cut out of the deal around the time that Australia begins to operate leased US Navy Virginia-class submarines.