From catastrophic military interventions in Iraq and Afghanistan to dictatorship-enabling, Kissinger-led subterfuge in Chile and Argentina, the US’s role as the “world’s policeman” since the aftermath of the conflict-ridden 1930s and 1940s has been far from flawless.

But domestic political pressure to disengage from ‘forever wars’ and cut foreign spending birthed a trend of US isolationism, epitomised by the withdrawal of troops from Afghanistan in 2021 which allowed the Taliban to regain control.

How well do you really know your competitors?

Access the most comprehensive Company Profiles on the market, powered by GlobalData. Save hours of research. Gain competitive edge.

Thank you!

Your download email will arrive shortly

Not ready to buy yet? Download a free sample

We are confident about the unique quality of our Company Profiles. However, we want you to make the most beneficial decision for your business, so we offer a free sample that you can download by submitting the below form

By GlobalDataIt was short-lived. So far this year, the US has fought on more geopolitical fronts than at any other time in its history.

Escalating conflicts in Ukraine and Gaza have dominated headlines – and US military funding. But pressure from adversaries, including China, North Korea, Iran and Russia in the South China Sea, Korean Peninsula, Red Sea and Eastern Europe, has elicited an unexpectedly strong US presence in Japan, Germany, South Korea, Israel and other allies.

The intervention-isolation debate came to a head on 17 April when President Joe Biden admitted in a Wall Street Journal op-ed that the US “could be drawn in” to sending troops to an all-out Middle East war – a remark far removed from the hands-off comments of his opposite number, Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump.

US military deployment depends on whether Iran escalates the conflict with Israel beyond the 13 April airstrikes, most of which Tel Aviv repelled with the help of US, UK and Jordanian warplanes.

Israel retaliated with a missile strike on the Iranian city of Isfahan on 19 April. Tensions have slightly cooled this week, but the prospect of a response from Tehran – and subsequent US involvement – lingers over the region.

But, with its fingers in geopolitical pies across the Middle East, Indo-Pacific and Europe, is it possible that Washington’s hold on the global order could stretch to breaking point?

A hierarchy of allies

The US has 168,000 active-duty troops serving overseas (as of last September – this number may have increased significantly in the last seven months), spread across more than 750 bases in 80 countries.

The issue is not just that US troops are spread far and thin. Warfare is no longer determined by army size but rather by military technology – and, even if it was, the US could quickly mobilise troops.

Lawmakers in Washington see resources and diplomatic tension as more pressing issues.

On 24 April, Biden ended a months-long saga over aid for Ukraine, signing a bill to send Kyiv $61bn of air defence munitions, artillery, rocket systems and armoured vehicles.

The bill is designed to prolong aid for Ukraine even if Biden does not retain office after the US elections in November, says Carolina Pinto, thematic analyst at GlobalData.

“Biden isn’t following the traditional US interventionism with the national security bill”, Pinto tells Army Technology. “This bill is about securing foreign aid before the elections, so regardless of the result, the US can continue to militarily support Ukraine and Israel. Truth be told, Ukraine is completely dependent on foreign support, with the US providing almost 50% of Ukraine’s military aid.”

While Ukrainians welcomed it, sceptical Republican lawmakers say the bill is futile, merely prolonging a war which Russia remains likeliest to win.

Biden’s rationale that “it’s going to make America safer, it’s going to make the world safer, and it continues America’s leadership in the world” has not assuaged concerns that Washington may be overstretching.

The US’s diplomatic clout is significant, but – like the number of troops and military resources – it is finite.

Recent aid packages and military interventions have indicated a clear hierarchy of the US’s alliances, drawing the disgruntlement of some allies.

This latest bill may earmark more money for Ukraine ($61bn) than Israel ($14.1bn) or Taiwan ($3bn), but Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky was quick to complain when the US, UK and other Western allies deployed warplanes to defend Iran’s attack on Israel, having refused to make the same commitments to neutralise Russia’s aerial bombardments.

“Shaheds in the skies above Ukraine sound identical to those over the Middle East,” Zelensky wrote on X. “The impact of ballistic missiles, if they are not intercepted, is the same everywhere.”

Indo-Pacific priorities

Crossed diplomatic lines – and the threat of China – have left Washington seeking to shift more of the Ukraine burden onto European shoulders, according to Christopher Granville, managing director of global political research at TS Lombard.

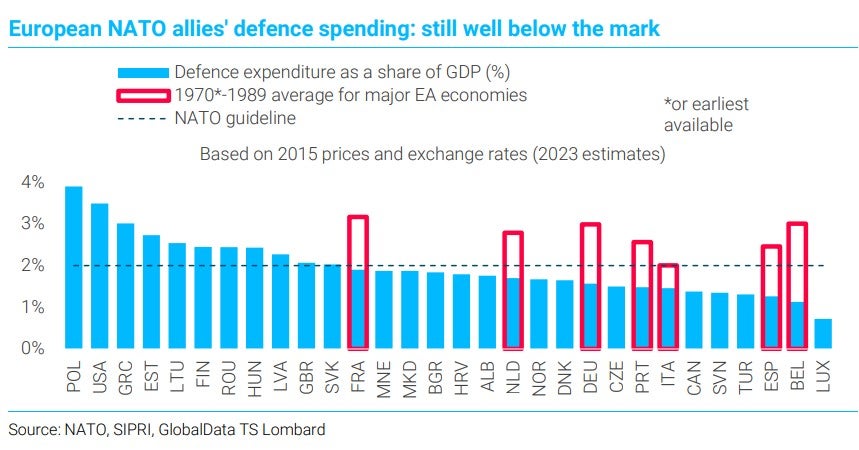

“The greater burden sharing in security and defence spending expected from wealthy European allies should from now on be seen as part of a broader division of labour, whereby Europe bears the main burden of countering the Russian threat in its own neighbourhood freeing up the US to focus more on its key ‘pacing challenge’ regarding China”, Granville tells Army Technology.

Germany, at least, seems to have acknowledged this challenge. Ukraine’s second-largest benefactor pledged further aid in the form of a Patriot interceptor, batteries and radars last week.

“Europe, however, does not have the stockpiles let alone the manufacturing capacity to replenish Ukraine’s gaping holes by itself”, Granville adds.

Biden appears keen to push Nato members to prioritise defence, although he is not as openly hostile on the matter as Trump.

In February, the former US President sparked outrage by stating that, if he returns to the White House office, he would encourage Russia to do “what it damn well likes” to any European country which spends less than the Nato-stipulated 2% of GDP on defence.

Biden condemned Trump’s remarks as outrageous, but has unequivocally signalled it is time for the US to redouble efforts to counterweigh Beijing.

Indo-Pacific tensions have been inflamed by increasingly aggressive Chinese naval action in the heavily disputed South China Sea, where Taiwan, the Philippines, Japan, Vietnam, Malaysia and Brunei also have competing territorial claims.

Beijing seeks to consolidate control along its infamous ‘nine-dash line’. Recent ploys have varied from the ramming and targeting of Filipino ships with military-grade lasers and water cannons to opening two new flight routes over Taiwan.

In response, the US has strengthened ties with allies in the region, meeting first with Japanese Prime Minister Kishida Fumio, then the day after (April 11) with Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos Jr in the White House.

As both meetings took place, a US carrier strike group held a two-day joint exercise with military forces from Japan and South Korea, which Beijing’s foreign office described as “irresponsible and extremely dangerous”.

Japan and South Korea’s willingness to cooperate on military drills is emblematic of just how wary both countries are of China – and North Korea, which has ramped up weapons testing in recent months. Japan’s 35-year colonisation of the Korean Peninsula still lingers in the memory of South Koreans, sometimes straining the relationship between the two US allies.

“Iron-clad” support for Israel strains US global image

Recently, Washington has encountered greater difficulties in balancing the geopolitical dynamic of its European and Middle Eastern allies than Indo-Pacific partners.

Despite Nato members’ shared aims, divisions have grown over incidents including the leaked German military call revealing UK troops are “on the ground” in Ukraine, and French President Emmanuel Macron calling on European nations “not to be cowards” in considering troop deployment to defend Ukraine.

There is also mounting global discord over the supply of weapons to Israel, which China and Russia have largely managed to steer clear of.

On 25 April, the UN called for an international investigation into the discovery of mass graves at two Gaza hospitals, where Palestinian authorities say Israeli military forces buried more than 400 bodies.

“Among the deceased were allegedly older people, women and wounded, while others were found tied with their hands…tied and stripped of their clothes,” said Ravina Shamdasani, spokesperson for the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights.

As the Israel-Gaza conflict approaches its seventh month, claiming more than 34,200 lives, this latest accusation of an Israeli war crime has intensified calls to cease arms shipments.

Japan, Spain, Canada, the Netherlands and Belgium have all said they will stop shipping weapons to Israel, while Denmark is considering suspending the export of F-35 fighter jet parts to the US because it sells the finished jets to Israel.

The US’ “iron-clad” support for Israel has been a key factor behind its transition from direct intervention in Middle Eastern wars in the early 2000s to proxy intervention through arms exports and diplomatic rhetoric.

But there is growing resentment towards the US’s seeming willingness to give Israel free rein to carry out its offensive in Gaza in whatever manner Prime Minister Netanyahu chooses.

As the clamour reaches boiling point, Washington may be left to decide between standing by long-time ally Israel or placating its wider network of geopolitical allies across Europe and the Indo-Pacific.